12 июля 2020 от nrg345

Оригинальное название: Alpsee

Год выхода: 1995

Жанр: экспериментальный, короткометражный

Режиссёр: Matthias Müller

В ролях:

Christina Essenberger, Victor Helpap

Plot:

For a young boy, ordinary facts and things of daily life seem to have great importance.

Alpsee transportiert komplexe, heftige Emotionen durch den Einsatz einfacher Elemente, gleichzeitig reflektiert er eine historische Filmära und ruft die Realität der fünfziger Jahre ins Gedächtnis. Indem er die Bedeutung von Dingen überstrapaziert und durch seinen Einsatz von Farben erforscht er eine Welt von primären Instinkten. Die latente Spannung zwischen der semantischen Bedeutung von Gewalt und Einsamkeit einerseits und dem klaren Ausdruck andererseits, wird er zum Ende hin sehr entschlossen, wo Emotionen die Struktur des Films prägen. Während sich der Film an eine andere historische Epoche wendet, gelingt Alpsee die Darstellung sehr fundamentaler Themen.* * *

Alpsee (15 min 1994) is Müller’s latest offering, a revisitation of the filmer’s own Final Cut, rendered now in an elegant, high-gloss style and shimmering colour palette learned from the 50s. Like Final Cut, Alpsee turns about the relation of mother and son, but while the former devolves into a granular first person universe, the latter utilizes dramatic rhetoric to narrate the rhythmic interplay between a young boy’s longing and his maternal filigree. It opens with a collection of Technicolor home movies, young women caught in the throes of graduation, being led by their elders past the threshold of their own childhood.

The image ripples and waves, subject to electronic re-processing, a subtle movement of undulation which gives way to the film’s next image – a long theatrical drape which fills the frame. Müller attaches the drape’s monochromatic insistence with the dress of the mother, glimpsed in close-up, who then retreats from the camera. She tries on a ring before the blue drapes appear once more, opening to reveal a young child. Again, the mother’s blue dress floats through the living room as she puts on a record, dusts, and closes cupboards in a percussive polyphony that makes of these home-made gestures a symphony of the domestic. She irons, puts cherries on a pie and continues to close cupboards until the camera floats away to a television in a dark and neighboring room. It shows an operation, the flesh torn away to reveal pulsing organs, with a voice blandly intoning, “What we have here is a human heart”.

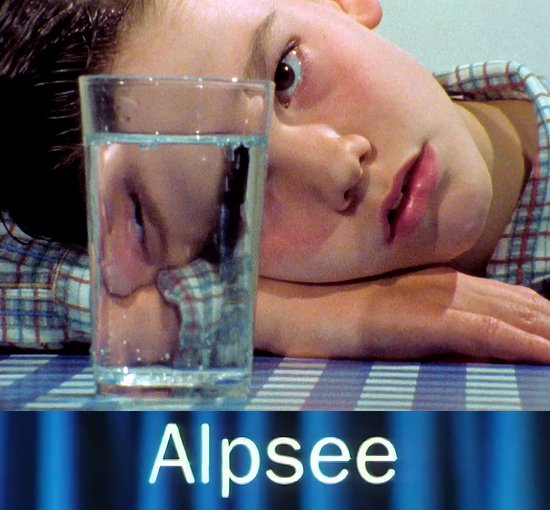

The boy opens a small box which contains porcelain figures of a married couple, an iconic reminder of life as it was meant to be, which underscores the absence of the father in their life together. The boy retires to read through an encyclopedia filled with images of trees – family trees perhaps – before a space movie interrupts, astronauts look on in astonishment as a plant takes flower. “Watch this! A flower has grown on planet Mars! It’s a miracle.” These dreams of space prompt him towards his own dream of horticulture. Alone, in a vast forest, he secures his own plant, wondering if the distance between ancestors has converted his family into something as alien as Mars. Later, his mother pours off a glass of milk which soon overflows, unable to embrace the contents of the pitcher. This scene is lifted directly from Final Cut, though its significance is clearer here.

The milk is emblematic of all his mother will pass on, but he isn’t ready yet, his glass is still too small, so the milk spills everywhere – running over the smooth chromatic surfaces of the table, floor and stairs, and finally engulfing the whole house. This imaginary lapse is abruptly arrested as he is glimpsed again, trying to join the pieces of the broken pitcher, attempting to restore an original wholeness, broken now in the absence of his father. From the pitcher he turns to a jigsaw puzzle, its small inscrutable fragments an ensign for his own confused responsibilities.

At night, as the mother again closes shutters and doors in rhythmic proliferation, he watches a growing stain seep across his bed, before he enters into it and begins again to dream. His imaginary carries him to a blackboard filled with starry charts and astronomical signs before he floats skywards, into unknown moons and galaxies. There he presides over a starry found footage montage of mothers and sons, each mother clutching their son lovingly to their breast. The next day he walks with a floral bouquet and lays it on his mother’s blue dress and the mother appears a last time standing before curtains, now changed in colour from blue to red before the film’s last shot – a woman bathing in a uniformly red sea.

Photographed with an exquisite eye for interiors and a restless invention, Alpsee stages a boy’s coming of age, that painful rend between infant dependency and mature individuation. Nearly wordless, Müller proceeds by analogy and synecdoche, gathering up precisely framed moments within the home and collecting them as evidence. Its gorgeous chromatic scheme and high key lighting mark a significant departure from Müller’s narrow gauge efforts of the 80s, yet he maintains his characteristic syncopation, his grand eye for detail, and his resolute focus on the traumas underlying his subject. Like the blank couple of Continental Breakfast, the young boy in Final Cut, the shadowy figures in Epilog and Aus Der Ferne, Müller reinvests the everyday with a trauma that is alternately historical and familial. That his empathy with his subjects is so perfectly borne into the apparatus of a materialist film practise, makes him one of the fringe’s most powerful and most perfect makers.

Originally published in Millennium Film Journal No. 30/31, Fall 1997

Производство: Германия (Matthias Müller, Bielefeld)

Продолжительность: 00:13:29

Язык: немецкий

Файл

Формат: MP4

Качество: WEB-Rip

Видео: AVC, 640x480, 25 fps, ~660 kbps, 0.086 bit/pixel

Аудио: AAC, 44.1 kHz, 2 ch, ~152 kbps

Размер: 79 MB

Уважаемый пользователь, вам необходимо зарегистрироваться, чтобы посмотреть скрытый текст!

Plot 2

Plot 2