17 июня 2019 от blues

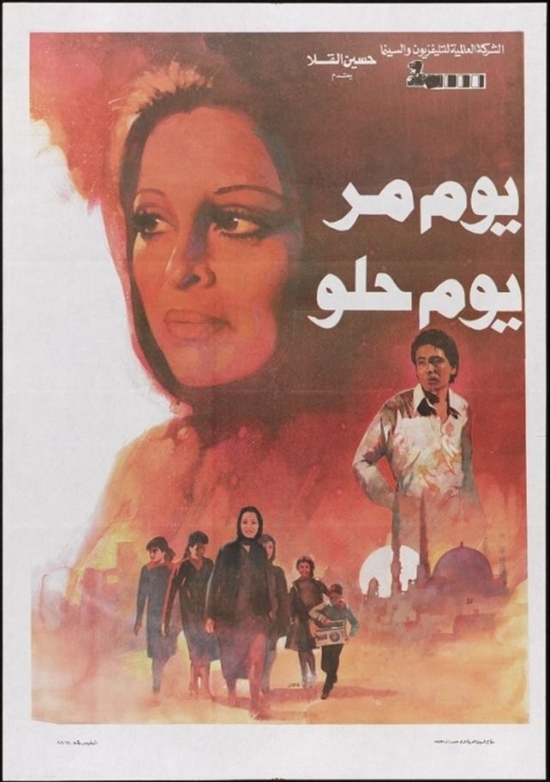

Оригинальное название: Yom mor... yom helw

Английское название: Bitter Day, Sweet Day

Год выхода: 1988

Жанр: драма

Режиссёр: Khairy Beshara

В ролях:

Махмуд Эль Гинди / Mahmood El-Gindi, Фатен Хамама / Faten Hamamah, Mohamed Henedi, Ahmad Hussain, Abla Kamel, Lotfy Labib, Мохамед Мунир / Mohamed Mounir, Симона / Simone, Ханан Юссуф / Hanan Youssef

Описание:

Семья, состоящая из одинокой вдовы и пятерых детей, отчаянно борется с неумолимо надвигающейся нищетой.

A pioneer of Egyptian neorealist cinema, Khairy Beshara has often said he owes his understanding of “the real” to the years he spent working as a documentary filmmaker before making his first feature, Al-Awama 70 (Houseboat No. 70), in 1982.

Perhaps nowhere is this loyalty to the real more apparent in Beshara’s films than in his 1988 masterpiece, Yom Morr… Yom Helw (Bitter Day, Sweet Day), which he co-wrote with screenwriter and two-time collaborator Fayez Ghali. The film was inspired by a real incident Beshara remembers from his childhood in Cairo’s Shubra district – a girl in his neighborhood had set herself on fire, and everyone was talking about it but nobody knew why she had done it. The memory never left him, and later became the starting point around which he weaved the story of Bitter Day, Sweet Day, as well as the basis for one of its most memorable scenes.

Bitter Day, Sweet Day is Beshara’s fourth feature and the last he made before moving on to what he considers the second stage of his cinematic career, beginning with 1990’s Kaboria (Crab). With Kaboria, Beshara started taking his narratives in a new direction, marked by a hint of absurdity and a more pronounced conflict between two worlds, more often than not that of the working class and that of the bourgeoisie. Bitter Day, Sweet Day, on the other hand, like Al-Toq wal Eswera (The Collar and the Bracelet, 1986) before it, is set in one very particular world, and the story almost never leaves it, establishing a strong sense of place.

In its own way it is Beshara’s tribute to Shubra and the years he spent there, without which, as he said in a 2006 interview with Al Jazeera, he would be an entirely different person. Set specifically in Shubra’s impoverished Al-Assal district, the film follows Aisha (a marvelous performance by Faten Hamama) as she struggles – along with her son and four daughters – to pay off her late husband’s debts and make ends meet, against a poignant soundtrack of old classics like Mohamed Abdel Wahab’s Ana wel Azab w Hawak newly rendered on the saxophone. Yet this is more than the bittersweet story of hardship and motherhood than it appears to be at first glance: it’s a commentary on the interplay of sex and space, and the tensions that arise with lack of both.

From the very beginning, Aisha and her children are fighting for room: they are jostled on the streets of Cairo in long shots where we almost lose sight of their tiny figures in the gray frenzy of traffic, and they stumble into and squeeze past one another in the narrow corridor of their small apartment, which, we come to realize, is the core of the film’s conflict. The catalyst is the relationship between Sanaa (Hanan Youssef), one of the daughters, and Oraby (Mohamed Mounir), the loudmouthed, unabashedly greedy carpenter she is engaged to, and what it entails for the rest of the family: When Oraby announces he doesn’t have enough money to buy a place for himself and Sanaa as promised, Aisha is left with no choice but to relinquish part of her family’s space and allow him to move into the house, which – like the city itself – is already overcrowded.

A sense of claustrophobia is palpable throughout most of the scenes filmed in the house, emphasized by the deliberate camera work of Tarek al-Telmissany, and eased only by the presence of the large window in the living room, with its colorful panes of glass. Yet even when the window is open, we are only exposed to a dark alleyway and more cement. There’s no relief. This window becomes the physical center of the film, bearing witness to nearly all the significant moments — it is through it that Oraby enters the apartment with Sanaa on their wedding night, and it’s through it that he escapes after his final betrayal. It is also through that window that Aisha hears screaming one afternoon, and is informed by one of her neighbors that Umm Yehia, the vegetable seller with heart disease, has died after a dispute with her son over the apartment they shared. He wanted to get married and kick her out so he could live there with his bride. Again we’re reminded: living in Cairo is a constant battle for space, and one that may kill you.

In another scene by the window, Aisha tries, one last time, to talk her daughter out of marrying Oraby, and this is when we are introduced to the other, equally potent force driving the story. Sanaa tells her mother that she has needs she can no longer deny or ignore, and so Aisha no longer argues. This isn’t the only mention of sex — all three older sisters grapple with it in different ways. In one of the film’s most evocative moments, Soad (Abla Kamel) silently steps away when her mother starts to talk to her newlywed friend, Umm Doss, about married life. She understands that, as a young unmarried woman, she isn’t allowed to listen. Soad’s face is out of focus despite being in the foreground, yet we can still see her curiosity as she eavesdrops, her shy smile, almost mischievous. Earlier she had flirted with the milkman, then, after he tries to kiss her, got beaten by her brother, her mother and a jealous suitor. This is a world where women are constantly compelled to hide any trace of their sexuality, often with disastrous results: Unlike Soad, lucky enough to escape, Sanaa’s frustration pushes her into a marriage that gives an immoral, opportunistic man control over her family, while Lamia (Simone), increasingly aware of her feminine appeal and hungry for an outlet, is reluctant to stop the advances of her sister’s husband.

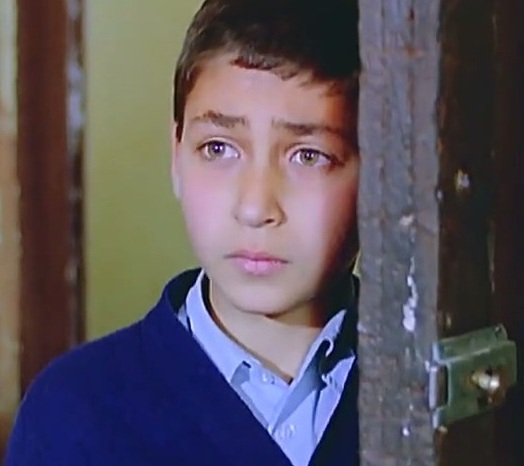

Yet if life in this world is kinder to men, it isn’t necessarily kinder to boys. Eleven-year-old Nour, Aisha’s youngest, is forced to drop out of school to become “the man of the house” and help out with expenses. He works at a bakery, cleans cars, then helps out at a mechanic’s workshop, and in each of these jobs is abused or overworked. Nour’s coming of age becomes the story within the story, especially when he develops a friendship — and falls in love — with Nawal, the daughter of a doorman in one of the neighborhood’s buildings, who happens to be years older than he is. It is in Nour’s scenes, however — especially those he shares with Nawal — that the film finds its respite: the open spaces, the movement, the playful music, the general lightness as they ride a bike together through the streets or share an ice cream cone on a crowded pavement, or even as Nour angrily confronts her new, older boyfriend against a stunning backdrop of the citadel, then goes off to smoke a cigarette, eager to feel like an adult. Perhaps Beshara creates this liberating atmosphere around Nour’s character, as opposed to the feeling of confinement permeating the rest of the film, because Nour is still a child, his fate as yet unsealed. He may not be free, but at least he has the promise of possibility.

It’s one of the many virtues of Bitter Day, Sweet Day that it often allows humor to find its way in, despite the grimness we’re all too aware of throughout. Umm Doss’s wedding dress ripping during the church ceremony, sewage water drowning the street during another wedding as the neighborhood’s kids play video games, Oraby’s crass fixation on cold watermelons — such are the delightful details that give the film its “flavor” (a word Beshara himself often uses), lending it power despite the absence of a clear-cut plot, standing witness to Beshara’s unwavering and career-defining ability to find poetry in the prosaic.

В этом женском царстве младшенький - единственный мужчина, и вынужден взвалить заботу о семье на свои юные плечи; взрослый мир встречает его сурово.

Производство: Египет

Продолжительность: 02:01:03

Язык: арабский

Файл

Формат: MKV

Качество: TV-Rip

Видео: AVC, 854x480 (16:9), 23.976 fps, 728 kbps, 0.074 bit/pixel

Аудио: AAC LC, 44.1 KHz, 2 ch

Размер: 743 MB

Уважаемый пользователь, вам необходимо зарегистрироваться, чтобы посмотреть скрытый текст!

Plot

Plot